Monday, January 31, 2011

Was Herman Melville a Novelist?

Please bear with me. Today, thanks partly to Melville, we're accustomed to thinking of the novel as a highly varied form. In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, Life: A User's Manual, and Gilead are all tossed into the "novel" category. But the essence of the form, its prime examples, are the 19th-century mirrors of society -- books like Middlemarch, Anna Karenina, and Uncle Tom's Cabin. These focused on realistic settings and plots, with stories driven by the interactions of fully developed characters.

We can look at Moby-Dick and find evidence of the foregoing items: realistic settings? yes; realistic plot? for the most part, yes; character-driven story? to a certain extent. The answers need to be qualified because so much of Moby-Dick is not a novel. Great stretches of it more closely resemble philosophy or natural history or even lexicography. Moby-Dick the novel becomes engulfed in a kind of Reader's Guide to Moby-Dick.

In fact, I would argue that Melville never wrote anything that fits neatly in the novel class. His first two books, Typee and its sequel, Omoo, were openly autobiographical (though scholars have since detected ways in which Typee uses published materials to embellish what Melville actually experienced). His fourth and fifth books, Redburn and White Jacket, were lightly fictionalized autobiographical accounts. In all four books, the plots are not much beyond "what happened to me when I lived with the headhunters/bummed around the South Pacific/first sailed in a merchantman/sailed in a U.S. frigate."

Whenever Melville attempted to steer away from retellings of his own experiences, he could not bring himself to stick with the traditional novel form. Mardi starts out comfortably enough as a sea story that brings Joseph Conrad to the modern reader's mind. But somewhere in the middle, Melville abandons the blueprint he's been following and starts on an entirely different structure, giving us a series of social-political satires in the form of allegories. Moby-Dick, while much more consistent and carefully planned than Mardi, nevertheless involves a similar massive non-novelistic superstructure resting upon a straightforward adventure story. After Moby-Dick came Pierre, in which Melville's dissatisfaction with the traditional novel completely boils over. What begins as a gothic romance in the style of Anne Radcliffe and Charles Brockden Brown turns into a homicidal (and suicidal) attack on popular literature, the publishing industry, and Pierre itself.

Melville's remaining "novels" don't strengthen the case for Melville = novelist. The novelistic skeleton of Israel Potter was largely lifted from another source. The Confidence-Man, like the second half of Mardi, is a series of vignettes rather than a novel. Finally, there's Billy Budd, which is barely long enough to qualify as a "real" novel.

One view is that Melville was, at heart, a poet. He certainly had the talent. But he also had a critic's drive to pick apart and reinterpret the world around him. In that regard, he would have fit well with the great Victorian social critics, Carlyle, Macaulay, Arnold, and others. Sadly, his lack of formal education unfitted him for that role. He suffered as he struggled to find a mode of expression that would be both artistically satisfying and commercially successful. That struggle produced at least one masterpiece and decades of agony.

Latest News from the Feejees

Another film version of Moby-Dick was shot in Nova Scotia and Malta in 2009, with William Hurt as Ahab, Gillian Anderson as Ahab's wife ("Elizabeth"), Ethan Hawke as Starbuck, one of those Hobbit dudes, etc.

The local newspaper in Nova Scotia has extensive coverage. It is reported to be a 4-hour TV mini-series. No mention of an air-date.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Snowbound While Working on Moby-Dick

I have a sort of sea-feeling here in the country, now that the ground is all covered with snow. I look out of my window in the morning when I rise as I would out of a port-hole of a ship in the Atlantic. My room seems a ship's cabin; & at nights when I wake up & hear the wind shrieking, I almost fancy there is too much sail on the house, & I had better go on the roof & rig in the chimney.-- from a letter by Melville to Evert Duyckinck, Pittsfield, Mass., Dec. 13, 1850

Moby-Dick Ephemera at the Sign of the Iron-bound Bucket

IBB was also kind enough to link to Ahab Beckons, for which, thank you!

("Iron-bound bucket" is an allusion to Ch. LXXVIII, "Cistern and Buckets." A very apt image for a blog about Moby-Dick, I can assure ye.)

Saturday, January 29, 2011

"And I only am escaped alone to tell thee."

The intended works of man and the unintended works of nature may collide tragically. We sail into the middle of the Pacific Ocean to harvest whales for oil, and one such animal bursts the hull of our ship, leaving us suddenly stranded in tiny boats thousands of miles from land. We launch a spaceship into orbit, and cold weather shrinks the ship's gaskets, causing it to disintegrate and kill the crew. Thus do the impersonal forces that surround us doom in an instant our high ambitions and brave venturings far from shore.

Captain Ahab thought those forces weren't so impersonal after all. Starbuck differed with him: "'Vengeance on a dumb brute!' cried Starbuck, 'that simply smote thee from blindest instinct! Madness! To be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous.'" But Starbuck's objection did not arise from any sort of modern agnostic materialism, in which mere energy and particles account for everything. After all, Starbuck calls Ahab's anger blasphemous. There can be no blasphemy without the divine.

Rage against a dumb brute seems blasphemous to the orthodox Starbuck because ... well, the simple explanation might be that since all creation is under God's direction, rage against a part of creation is rage against God. Indeed, that is exactly why Ahab is enraged -- he wants to "strike through the mask" of the created world to hit the Creator. The less simple explanation is that rage against a force of nature, no differently from worship of a force of nature, elevates the force into a god. Ahab has abandoned the God of Starbuck -- the God of George Fox, William Penn, and the good Quakers of Nantucket -- for an adversarial, animistic god who is bound by no covenant.

Natural disasters, more than man-made tragedies, raise the problem of evil. If there is a god, and it's the God of Starbuck, why does He cause or allow earthquakes, plagues, whaleship sinkings, and O-ring failures? How does the undeniable human suffering that results serve His plan?

The Book of Job, from which the headquote to Ishmael's epilogue is taken, provides one answer, the answer of a man who has seen, felt, and thought much in this world:

Then the LORD answered Job out of the whirlwind, and said,

Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge?

Gird up now thy loins like a man; for I will demand of thee, and answer thou me.

Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? declare, if thou hast understanding.

* * *

Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down?

Canst thou put an hook into his nose? or bore his jaw through with a thorn?

Will he make many supplications unto thee? will he speak soft words unto thee?

Will he make a covenant with thee? wilt thou take him for a servant for ever?

Wilt thou play with him as with a bird? or wilt thou bind him for thy maidens?

Shall the companions make a banquet of him? shall they part him among the merchants?

Canst thou fill his skin with barbed irons? or his head with fish spears?

Whatever we are, however strong our sailing ships and powerful our spaceships, we aren't gods. A dumb brute, a particle of frost, a cancer cell can cripple us and wreck our works.

Friday, January 28, 2011

Higgledy-Piggledy Whale Statements

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Melville and Albert Pinkham Ryder

Melville moved his family to New York City in 1863, some 12 years after the publication of Moby-Dick. Ryder (who was almost 30 years Melville's junior and was born in, of all places, New Bedford) moved to New York City in 1867 or '68. Never marrying, he led a reclusive life.

Most of Ryder's paintings are relatively small, heavily worked, dreamlike and expressionistic. They present nightmares to conservators because he had a habit of adding new layers of paint before the earlier layers had completely dried. Even today, some of his works are still not thoroughly dry. He disdained crowd-pleasing academicism and stubbornly pursued his private obsessions.

One of Ryder's most Melvillean paintings is Jonah, in the Smithsonian's collection. It has become so darkened over time that some details can barely be made out. In the foreground swims Jonah, waving his arms, as the great fish bears down upon him (the creature's eyes and snout can just be discerned in the far right of the painting, about halfway up). Up above, a transcendent God can be seen directing or sanctioning the course of events. It would be hard to imagine a more fitting illustration for Chapter IX, "The Sermon."

I once asked the Ryder expert William Innes Homer if he thought Ryder and Melville knew each other. He said that an acquaintance between the two men would certainly be no surprise, given their geographical proximity and their apparently similar artistic temperaments and interests. But, he went on, as far as he was aware, there is no evidence that they knew each other, or even that each had any idea of the other's existence.

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Another Report on the 2011 New Bedford Moby-Dick Marathon

A writer named Meera Subramanian attended the entire Moby-Dick marathon this year and has posted a thoughtful account of her experience, with pictures, at Killing the Buddha. Interestingly, she had never read Moby-Dick before. Nonetheless, she seems to have had quite a good time:

A writer named Meera Subramanian attended the entire Moby-Dick marathon this year and has posted a thoughtful account of her experience, with pictures, at Killing the Buddha. Interestingly, she had never read Moby-Dick before. Nonetheless, she seems to have had quite a good time: Some of the readers in New Bedford were born preachers .... They read neither too slow nor too fast. They lingered over words. They savored the stage directions of punctuation. Others were young, or inexperienced, or melodramatic. The resulting flavors were humorous (when an English captain took on a thick Brooklyn brogue) or painful (when the most basic words were mispronounced, prompting one friend to quip, “So that’s how Latin turned into English.”). Yet there was always something fabulously democratic about the mélange. Our lack of reading aloud, or perhaps more accurately, our lack of listening, is the death of our pronunciation. Moby-Dick is advanced; there are deceptive nautical terms where only half the letters are pronounced and 25-cent words galore. When they were spoken correctly, they sang. We listeners learned.

The "stage directions of punctuation" is a nice touch.

HT: New Bedford Whaling Museum blog.

Melville and Liverpool's Nelson Monument

The ornament in question is a group of statuary in bronze, elevated upon a marble pedestal and basement, representing Lord Nelson expiring in the arms of Victory. One foot rests on a rolling foe, and the other on a cannon. Victory is dropping a wreath on the dying admiral's brow; while Death, under the similitude of a hideous skeleton, is insinuating his bony hand under the hero's robe, and groping after his heart. A very striking design, and true to the imagination; I never could look at Death without a shudder.The photo on Wikipedia does not do the sculpture justice. Instead, enjoy a fine series of photos on Flickr, starting here.

At uniform intervals round the base of the pedestal, four naked figures in chains, somewhat larger than life, are seated in various attitudes of humiliation and despair. One has his leg recklessly thrown over his knee, and his head bowed over, as if he had given up all hope of ever feeling better. Another has his head buried in despondency, and no doubt looks mournfully out of his eyes, but as his face was averted at the time, I could not catch the expression. These woe-begone figures of captives are emblematic of Nelson's principal victories; but I never could look at their swarthy limbs and manacles, without being involuntarily reminded of four African slaves in the market-place.

And my thoughts would revert to Virginia and Carolina; and also to the historical fact, that the African slave-trade once constituted the principal commerce of Liverpool; and that the prosperity of the town was once supposed to have been indissolubly linked to its prosecution. And I remembered that my father had often spoken to gentlemen visiting our house in New York, of the unhappiness that the discussion of the abolition of this trade had occasioned in Liverpool; that the struggle between sordid interest and humanity had made sad havoc at the fire-sides of the merchants; estranged sons from sires; and even separated husband from wife. And my thoughts reverted to my father's friend, the good and great Roscoe, the intrepid enemy of the trade; who in every way exerted his fine talents toward its suppression; writing a poem ("the Wrongs of Africa"), several pamphlets; and in his place in Parliament, he delivered a speech against it, which, as coming from a member for Liverpool, was supposed to have turned many votes, and had no small share in the triumph of sound policy and humanity that ensued.

How this group of statuary affected me, may be inferred from the fact, that I never went through Chapel-street without going through the little arch to look at it again. And there, night or day, I was sure to find Lord Nelson still falling back; Victory's wreath still hovering over his swordpoint; and Death grim and grasping as ever; while the four bronze captives still lamented their captivity.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

How to Be a Good Moby-Dick Marathon Reader, Part 2

Hence the next principle in our ongoing series:

Rule 2: Speak the text, the whole text, and nothing but the text.

Your responsibility as a reader is to pick up where the previous reader left off and to read on until you're signaled to stop, when the next reader takes up the burden. The entire marathon should comprise an unbroken series of different voices that together take us, without frolics or detours, from "Call me Ishmael ..." to "... only found another orphan."

When you read, therefore, you should adhere religiously to what Melville wrote. The words that he set down, in the arrangements he selected, move us and inspire us to sustain this communal experience. Without his text, we are become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

Ideally, nothing in Moby-Dick should be omitted. In practice, however, some things are. The introductory "Etymology" and "Extracts" are deliberately excluded, as I've discussed. The handling of chapter titles and Melville's footnotes varies from reader to reader; some skip them, others do not. I would prefer that readers not skip chapter titles and especially not footnotes. A much more serious matter is the occasional accidental skipping of text. Readers have been known to skip a couple of paragraphs by accident. No one likes that, but it is usually allowed to pass in silence. In 2010, however, one reader skipped so much text (presumably by turning several leaves at once) that the "watch" stopped her and asked her to go back.

By the same token, nothing should be added to what Melville wrote. The audience wants no jocular asides, no dedicatory prefaces, no autobiographical embellishments, no pleas for indulgence, no shout-outs to peeps. The participants in the New Bedford marathon take their Melville straight. He provides more than enough commentary and wit for anyone, and doesn't need our feeble efforts to "improve" upon his work.

Monday, January 24, 2011

Dangerous Work

We gave a look aloft, and knew that our work was not done yet; and, sure enough, no sooner did the mate see that we were on deck, than—"Lay aloft there, four of you, and furl the top-gallant sails!" This called me again, and two of us went aloft, up the fore rigging, and two more up the main, upon the top-gallant yards.

The shrouds were now iced over, the sleet having formed a crust or cake round all the standing rigging, and on the weather side of the masts and yards. When we got upon the yard, my hands were so numb that I could not have cast off the knot of the gasket to have saved my life. We both lay over the yard for a few seconds, beating our hands upon the sail, until we started the blood into our fingers' ends, and at the next moment our hands were in a burning heat. My companion on the yard was a lad, who came out in the ship a weak, puny boy, from one of the Boston schools,—"no larger than a spritsail sheet knot," nor "heavier than a paper of lamp-black," and "not strong enough to haul a shad off a gridiron," but who was now "as long as a spare topmast, strong enough to knock down an ox, and hearty enough to eat him." We fisted the sail together, and after six or eight minutes of hard hauling and pulling and beating down the sail, which was as stiff as sheet iron, we managed to get it furled; and snugly furled it must be, for we knew the mate well enough to be certain that if it got adrift again, we should be called up from our watch below, at any hour of the night, to furl it.

TYBTM was published in 1840, some six years before Melville's first book, Typee, and nine years before Melville's first book-length portrayal of the merchant service, Redburn. By the time Melville was writing, Dana had already produced the ultimate reportorial expose of the sailor's life aboard ship. There was nothing more anyone could say in that line. Nor did Melville try; Redburn is much more psychological than TYBTM, and much more atmospheric. In Dana's book, you forget you're viewing the world through someone else's eyes; in Melville's, you can never escape his gray, drizzly mood suffusing everything.

Suffering laborers at sea remind me of suffering laborers on land. Before the invention of air brakes in the early 20th century, the railroad brakeman had to run along the tops of freight cars, summer and winter, to turn the brakes by hand. Not a few unfortunate men fell between the cars and were mangled. This webpage has evocative brakeman lore, to help us keep things in perspective.

Today in History

Three of the hands of the brig Rainbow (a New Haven vessel) on shore on Point Judith, have been frozen to death.

Focusing the Mind at 4:00 am

Someone in some book I read a number of years ago (maybe it was this one) remarked upon the surreal feeling of being in an office building at 2:00 in the morning. The tomb-like silence, the stillness outside, and the gloom in the hallways make you feel as if you're the only person on Earth.

This sense of aloneness may be what makes the Graveyard Shift at the Moby-Dick marathon unusually appealing (for me, at least). On the one hand, the threat of abandonment in the vast dark, like Pip floating in the sea, left behind by the whale boats -- "The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul." (Ch. XCIII, "The Castaway.") On the other hand, the closed-in campfire circle of devoted readers, listeners, and organizers. Centrifugal and centripetal forces, they hold you in place by pulling in opposite directions, as you sit on the edge between light and dark, waking and sleep.

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Facing the Podium at the Moby-Dick Marathon

Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that

brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did

it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a

prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove

fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men,

and great Achilles, first fell out with one another.

- The Iliad, Book 1

Saturday, January 22, 2011

WiFi in the Museum

Web-addicts take note: the Whaling Museum made its WiFi network available during MDM15, enabling attendees to blog in real-time or check the pronunciation of "Euroclydon."

There are a few power outlets around the edges of the rooms, but these could become scarce resources at future readings. (Consider bringing a power strip to share the juice with your shipmates.)

Moby-Dick Web Sighting

You say Harpooner...

- "harpooneer" appears 12 times, both in direct speech and in descriptive text. This includes one appearance in a footnote, and one in "Extracts."

- "harpooner" appears 62 times, both in direct speech and in descriptive text.

How to Be a Good Moby-Dick Marathon Reader, Part 1

When you register, no one inquires into your qualifications or lack thereof. They don't even ask if you've read Moby-Dick or are a member of the museum. Not unlike a Quaker meeting, where the Inner Light might move anyone to speak, the marathon denies nobody who registers the opportunity to be heard. Eloquence or learning is not a prerequisite.

Just as not everyone is a born preacher, not everyone is a born reader. The quality of marathon readings varies as much as the backgrounds of the volunteers. Still, I believe it's possible to agree on a handful of principles that, if observed, will help you read in a most pleasing manner. We will propose these principles from time to time in a series of posts.

Rule 1: Do not shout.

The podiums at which the readers stand are equipped with sensitive microphones. They will pick up and amplify perfectly well whatever you say in a normal speaking voice. If you come on board "shouting like a boatswain in a gale of wind," the amplified sound will knock the listeners out of their chairs. It's painful. The back row will hear you fine without shouting.

Just stumbled on this blog...

Friday, January 21, 2011

The Graveyard Shift

Moby-Dick being what it is, a 600-ish page novel, it cannot be read in one sitting without including the wee hours of the morning. The fact that the New Beford Moby-Dick marathon is held in early January, when the nights are especially long and cheerless, only strengthens its right to hold itself out (should its organizers so choose) as the marathon of marathons.

I enjoy the Graveyard Shift more than any other part of the marathon. The beginning and end of the marathon are the crowd-pleasers. That's when the most novelistic and most accessible parts of the book are read. Ishmael meets Queequeg; Orson Welles (oops, I mean Father Mapple) gives his sermon in the Seamen's Bethel; Ishmael and Queequeg join the Pequod's crew; we meet Ahab, Starbuck, Stubb, Flask, Tashtego, and Daggoo; "Death to Moby Dick!" ... Then jump ahead 400 pages, we chase Moby Dick around the Pacific, "Ahab beckons" (well, maybe not), Finis. No shortage of readers and listeners for those parts of the book.

The Graveyard Shift attracts the die-hards. This is when we reach the chapters that casual readers are inclined to skip: "Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales" (Ch. LV); "The Great Heidelburgh Tun" (Ch. LXXVII); "Jonah Historically Regarded" (Ch. LXXXIII); "A Bower in the Arsacides" (Ch. CII). But those who stay up for the Graveyard Shift are treated to the rarefied pleasures of haute école expository Melville.

It is also at this time that every individual's contribution is most strongly felt. Those participating and following along can be taken in with one glance -- perhaps a dozen in all. Even if you don't speak to them, they become your comrades in a way that cannot happen when it's light outside and a crowd is on hand. The comedy of it, too, becomes most apparent. Sitting up at 3:00 am listening to people take turns reading Moby-Dick out loud -- how is this not ridiculous?

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Taking the Podium at the Moby-Dick Marathon

If you can tolerate gotcha TV, this display does contain some psychological interest. The complete lack of connection between how some people sound and how they think they sound raises intriguing questions about self-perception. It's hard to believe, but apparently true, that many people whose singing sounds like howling cats are nevertheless convinced they actually rival Judy Garland or [insert current pop singer of your choice].

Every January, I wonder if Moby-Dick marathon readers are similarly deluded. It has to be said that some readers are really quite bad, God bless them. They mean well; they're genuine Melville fans; they do the best they can. But no matter who you are, your best in certain endeavors just isn't very good. Indeed, your absolute best might be among the worst.

Do bad readers know they're bad? No one in the marathon audience ever gives any indication if someone's performance is less than stellar. Some bad readers do seem aware of the effect they're having, since I've seen a few gasp with relief when they're done, as if they'd just finished hacking a path through bamboo with a dull machete. If someone has such self-awareness, I can only respect her the more, even though my enjoyment is lessened. It's one thing for a person who reads out loud frequently and fluently to stand in front of a crowd of strangers and presume to read Moby-Dick to them. It's quite another thing for someone who knows he's a halting, stumbling reader to nonetheless risk humiliating himself in order to do his duty by Melville and the marathon.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Etymology and Extracts at the New Bedford Moby Dick Marathon

I guess I can see the logic behind this choice. The marathon, which now starts dramatically with an Ishmael impersonator (for lack of a better term) reading "Loomings" in the museum's Lagoda Room, would probably turn off many would-be participants if they had to sit through 15-20 minutes of non-narrative quotations from other authors before even getting to "Call me Ishmael."

Nevertheless, it doesn't seem right. A Moby-Dick marathon without "Etymology" and "Extracts" is like a Scarlet Letter marathon without "The Custom-House," or a Giles Goat-Boy marathon without the comic editors' statements on why they should or should not have published the manuscript. Is it really a marathon if you intentionally omit part of the text?

When I first raised this issue with Gansevoort, he suggested doing a "guerrilla reading" of "Etymology" and "Extracts" in front of the museum before the regular marathon begins. I like that in theory. But in the hour before the marathon, most people are too busy getting settled with their gear and what-not inside the building to have any time or attention to spare. Plus, New Bedford in January is not the best place for standing around reading or listening to yet more Melville.

Another possibility, now that the museum has started streaming the marathon, would be to have a virtual reading of the introductory material. Thus, even if it didn't happen live, a reading of the etymology and extracts would at least be part of the marathon in some sense. And I suppose a third possibility is simply to arrive early and read the etymology and extracts silently by oneself, while waiting for Ishmael to begin. Who knows, maybe some attendees do that already.

Monday, January 17, 2011

Mary Folger's grandson's birthday

No good blood in their veins? They have something better than royal blood there. The grandmother of Benjamin Franklin was Mary Morrel; afterwards, by marriage, Mary Folger, one of the old settlers of Nantucket, and the ancestress to a long line of Folgers and harpooners -- all kith and kin to noble Benjamin -- this day darting the barbed iron from one side of the world to the other.

Ben's mom, Abiah Folger, was also born in Nantucket. Somewhere on the moors of Nantucket, near the windmill, there's a monument marking her birthplace. She was the second wife of Ben's dad, and bore 10 children. Benjamin himself was Boston-born.

Why "Ahab Beckons" (Gansevoort's view)

[See Lemuel's previous post on this topic.]

[See Lemuel's previous post on this topic.]As Patti Smith told an interviewer who asked why she wore those strange clothes, "It looks cool."

As Lemuel suggests, confusion over the phrase "Ahab beckons," invented for a not-aimed-at-the-literati Gregory Peck period-revenge thriller (viewable online), shows how much a part of our culture Melville's original work has become. (Although I was shocked last month to find that my friend's college-junior daughter had never heard of the book or the movie. "What's Moby Dick?" A teachable moment, I guess.) Should we view Ray Bradbury's script as a mashup? (Doesn't that term sound quaint?)

Nor should we bookish types be smug. The prow-shaped pulpit in the Seamen's Bethel to which we troop for the reading of the "Father Mapple" chapters was only installed in 1961, in response to visitors' expectations after having seen the movie. (When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.)

Me, I'm a fatalist who loves a jolly memento mori.

Remember me as you pass by,And I love the complete quote from the movie: Ahab beckons. He's dead but he beckons. It calls to mind a favorite phrase from Samuel Beckett's The Unnamable: ...the ancient dead and the dead yet unborn...

As you are now, so once was I,

As I am now, so you will be,

Prepare for death and follow me.

But why say more? Ahab beckons each of us readers. Even Ishmael's story had its end.

Speaking of Beckett, here's another bit from The Unnamable that could have been in the mind of any of the Pequod's crew (as it was often in the mind of a certain corporate wage-slave, also on a rather long lay):

I, who might that be? The galley-man, bound for the Pillars of Hercules, who drops his sweep under cover of night and crawls between the thwarts, towards the rising sun, unseen by the guard, praying for storm.Morning to ye, shipmates, morning; the ineffable heavens bless ye...

How did they do it?

Why "Ahab Beckons"?

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD

In the 1956 film, the line "Ahab beckons" is spoken by Stubb (Harry Andrews), during the final chase of Moby Dick. Prior to this line, Ahab is knocked from his whaleboat, grabs the ropes streaming from Moby Dick to pull himself onto the whale's back, stabs the whale with a dangling harpoon while shouting two phrases taken verbatim from the book ("from hell's heart I stab at thee; for hate's sake I spit my last breath at thee"), and then becomes entangled in the ropes and drowns while bound to the whale's body. The three mates then see Moby Dick swim by, with Ahab's corpse plastered to his side, Ahab's dead arm flopping back and forth as the whale rolls. Hence, Ahab "beckons" to the sailors to follow him.

This makes for memorable cinema, but it bears little resemblance to what happens in the book. In the book, Fedallah (whom Bradbury excised in writing his version) is the one whose corpse the sailors (and Ahab) see lashed to Moby Dick's side. And there is no beckoning, even by Fedallah. His fate is instead tied by Ahab to a prophecy Fedallah had made ("Aye, Parsee! I see thee again," Ahab says. "Aye, and thou goest before; and this, THIS then is the hearse that thou didst promise."). What Bradbury apparently did was take bits of the Fedallah storyline and work it into his streamlined version, adding the visual touch of Ahab's waving arm.

Admittedly, an entirely faithful filming of Ahab's death would be quite underwhelming, since Ahab is jerked from this world in the blink of an eye ("voicelessly as Turkish mutes bowstring their victim, he was shot out of the boat, ere the crew knew he was gone").

END OF SPOILERS

So why would we title a blog devoted to the annual New Bedford Moby-Dick marathon with a movie line that has no analogue in the book itself? Gansevoort came up with the idea; I can't speak for his thinking. For myself, among other reasons, I think it reflects the gap between text and audience. Moby-Dick, more than other classics, demonstrates that a literary creation does not come with its own readership. Rather, it's at the mercy of the world it's launched into. Moby-Dick found a publisher, luckily, on the strength of Melville's earlier works, but it nearly sank like a stone on its first appearance. Some 50 years later, it was discovered and finally appreciated. It now remains a living classic, with real, non-academic readers, thanks partly to movies, the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and the museum's marathon.

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Herman Melville Sexual Orientation Watch, Part 1

As the world and I have grown older, and both of us have become more accustomed to discussing homosexuality and bisexuality in authors, I've come to find the question of Melville's sexual orientation (to use an anachronistic term) fascinating. Is it true what they say about relations between some men aboard sailing ships? Patrick O'Brian (in Master and Commander) and William Martin (in Cape Cod) certainly seemed to think so, although both were writing about war ships, not whalers.

Is Melville hinting at something that dare not speak its name in his fiction? Was he gay or bisexual? Was he a hetero gadfly with a transgressive sense of humor? Or is a harpoon just a harpoon?

I can't begin to formulate even a tentative answer to those questions. Someday I hope I will understand Melville better. In the meantime, I pick up bits of what appears to be evidence, for future study. For example, two passages from his 1849 novel Redburn: His First Voyage:

It was the day following my Sunday stroll into the country, and when I had been in England four weeks or more, that I made the acquaintance of a handsome, accomplished, but unfortunate youth, young Harry Bolton. He was one of those small, but perfectly formed beings, with curling hair, and silken muscles, who seem to have been born in cocoons. His complexion was a mantling brunette, feminine as a girl's; his feet were small; his hands were white; and his eyes were large, black, and womanly; and, poetry aside, his voice was as the sound of a harp. [Ch. XLIV]

* * *

There was on board our ship, among the emigrant passengers, a rich-cheeked, chestnut-haired Italian boy, arrayed in a faded, olive-hued velvet jacket, and tattered trowsers rolled up to his knee. He was not above fifteen years of age; but in the twilight pensiveness of his full morning eyes, there seemed to sleep experiences so sad and various, that his days must have seemed to him years. It was not an eye like Harry's tho' Harry's was large and womanly. It shone with a soft and spiritual radiance, like a moist star in a tropic sky; and spoke of humility, deep-seated thoughtfulness, yet a careless endurance of all the ills of life.

The head was if any thing small; and heaped with thick clusters of tendril curls, half overhanging the brows and delicate ears, it somehow reminded you of a classic vase, piled up with Falernian foliage.

From the knee downward, the naked leg was beautiful to behold as any lady's arm; so soft and rounded, with infantile ease and grace. His whole figure was free, fine, and indolent; he was such a boy as might have ripened into life in a Neapolitan vineyard; such a boy as gipsies steal in infancy; such a boy as Murillo often painted, when he went among the poor and outcast, for subjects wherewith to captivate the eyes of rank and wealth; such a boy, as only Andalusian beggars are, full of poetry, gushing from every rent.

Carlo was his name; a poor and friendless son of earth, who had no sire; and on life's ocean was swept along, as spoon-drift in a gale. [Ch. XLIX]

Where is credit due?

At the close of every MDM I wait for the credits to roll. Who are all these friendly folks, ministering angels, and stage managers who have kept us in a cocoon of care for the past 25 hours?

Good Behavior at the New Bedford Moby-Dick Marathon

The marathon proceeds in surprisingly good order, notwithstanding that it is free and open to all, in the heart of a modern city. I don't know what would happen if someone chose to disrupt it; I imagine there are city police ready to respond to serious trouble. But the fact is that the attendees behave themselves spontaneously.

But something else is at work as well, something peculiarly of New England. In his masterpiece Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, critic Edmund Wilson writes (in his chapter on Harriet Beecher Stowe) about "the crisis of Calvinist theology" in 19th-century New England, when the old-line Congregationalist ministers started losing large numbers of worshipers to more forgiving churches and denominations. Yet, as he also points out, the Calvinist mind-habits survived. Hard work, lawfulness, and the odd blend of self-reliance and community service did not vanish when the doctrine of predestination softened. Underneath the Emersonian kumbaya, it supplied the core of steel evident in the abolition movement and the Civil War.

We detect its vestiges today in Massachusetts, in orderly public events such as the Moby-Dick marathon. The mature gents and ladies who smoothly and quietly run the show, the volunteers who provide dinner and nighttime snacks with uncomplaining regularity, the readers who respectfully take us through Melville's creation, the listeners who peacefully follow along -- I don't believe quite the same picture could be seen anywhere outside New England.

Friday, January 14, 2011

A Second Opinion on Whalers

Putting the boat's head in the direction of the ship, the captain told us to lay out again; and we needed no spurring, for the prospect of boarding a new ship, perhaps from home, hearing the news and having something to tell of when we got back, was excitement enough for us, and we gave way with a will. Captain Nye, of the Loriotte, who had been an old whaleman, was in the stern-sheets, and fell mightily into the spirit of it. "Bend your backs and break your oars!" said he. "Lay me on, Captain Bunker!" "There she flukes!" and other exclamations, peculiar to whalemen. In the meantime, it fell flat calm, and being within a couple of miles of the ship, we expected to board her in a few moments, when a sudden breeze sprung up, dead ahead for the ship, and she braced up and stood off toward the islands, sharp on the larboard tack, making good way through the water. This, of course, brought us up, and we had only to "ease larboard oars; pull round starboard!" and go aboard the Alert, with something very like a flea in the ear. There was a light land-breeze all night, and the ship did not come to anchor until the next morning. As soon as her anchor was down, we went aboard, and found her to be the whaleship, Wilmington and Liverpool Packet, of New Bedford, last from the "off-shore ground," with nineteen hundred barrels of oil. A "spouter" we knew her to be as soon as we saw her, by her cranes and boats, and by her stump top-gallant masts, and a certain slovenly look to the sails, rigging, spars and hull; and when we got on board, we found everything to correspond,—spouter fashion. She had a false deck, which was rough and oily, and cut up in every direction by the chimes of oil casks; her rigging was slack and turning white; no paint on the spars or blocks; clumsy seizings and straps without covers, and homeward-bound splices in every direction. Her crew, too, were not in much better order. Her captain was a slab-sided, shamble-legged Quaker, in a suit of brown, with a broad-brimmed hat, and sneaking about decks, like a sheep, with his head down; and the men looked more like fishermen and farmers than they did like sailors.

Unpacking the New Bedford Moby-Dick Marathon: David Dowling's "Chasing the White Whale"

Prof. Dowling, who is also a marathon runner, attended the entirety of the 2009 marathon, where he recorded his impressions (including what it was like to be one of the readers, at 9:30 Sunday morning) and spoke with a variety of participants. His longest sustained discussion of the marathon occurs in the introduction. Thereafter, each chapter focuses on a different aspect of Moby-Dick and concludes with a section on a related aspect of the marathon.

He takes a very favorable, but not idealized, view of the event. He frankly admits, for example, that some of the readers are terrible (I believe that's the word he uses; I loaned my copy to Gansevoort and so can't readily check). Yet he's not at all condescending toward the marathon or the people who are into it. He admires its respectful ambience -- no Melville impersonators -- and its non-commercial, low-tech nature. Imagine, people sitting for hours just listening to someone read a book. Wonders never cease.*

Although Dowling never uses the term "folk art" (as far as I can recall), he seems to be headed in the direction of viewing the marathon as folk art or a folk ceremony. The New Bedford marathon, originally inspired by the one each summer at Mystic Seaport, was initiated by local citizens in their spare time and continues to be largely volunteer-run (although the New Bedford Whaling Museum certainly makes a generous, valuable, and much-appreciated donation in staff hours, expertise, promotion, and facilities). Thus, like Philadelphia's Mummers Parade or New York's Feast of San Gennaro or Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery," the New Bedford Moby-Dick marathon is an extra-market event rooted in local traditions and sustained by spontaneous, local impulses.

*Subsequent developments have undercut this particular point of Dowling's, since this year the museum introduced live web-streaming of the marathon. In addition, last year and this year, more and more e-readers (Kindles and iPads, especially) were spotted in use among the audience. Even the Moby-Dick marathon is not completely insulated from technological developments.

Thursday, January 13, 2011

New Bedford in Winter

Of course, one thing New Bedford has that those other cities don't is the New Bedford Historic District, in which the look of a Melvillean whaling port is kept alive. The streetcapes in the historic district evoke the New Bedford that Ishmael wandered through one December night:

Blocks of blackness, not houses, on either hand, and here and there a candle, like a candle moving about in a tomb. At this hour of the night, of the last day of the week, that quarter of the town proved all but deserted. ... Moving on, I at last came to a dim sort of light not far from the docks, and heard a forlorn creaking in the air; and looking up, saw a swinging sign over the door with a white painting upon it, faintly representing a tall straight jet of misty spray, and these words underneath—"The Spouter Inn:—Peter Coffin."Passages like this make me appreciate that New Bedford is not scrubbed and manicured, like some sort of Whaling Williamsburg. While the historic district has for the most part a touristy air to it, with upscale coffee shops and fern bars where Ishmael found warehouses and questionable accommodations, the rest of the city reminds us that Melville's New Bedford was (as it remains today) a working port. It was filled with working men, and no doubt working women, who labored aboard ships or in the trades that catered to them.

The frozen winds that blow through New Bedford's unkempt snow-encrusted streets also bring Ishmael sharply to mind:

[The Spouter Inn] stood on a sharp bleak corner, where that tempestuous wind Euroclydon kept up a worse howling than ever it did about poor Paul's tossed craft. Euroclydon, nevertheless, is a mighty pleasant zephyr to any one in-doors, with his feet on the hob quietly toasting for bed. "In judging of that tempestuous wind called Euroclydon," says an old writer—of whose works I possess the only copy extant—"it maketh a marvellous difference, whether thou lookest out at it from a glass window where the frost is all on the outside, or whether thou observest it from that sashless window, where the frost is on both sides, and of which the wight Death is the only glazier." True enough, thought I, as this passage occurred to my mind—old black-letter, thou reasonest well. Yes, these eyes are windows, and this body of mine is the house. What a pity they didn't stop up the chinks and the crannies though, and thrust in a little lint here and there.Trudging to and from the marathon in early January, along icy sidewalks that the low-rising, soon-setting sun barely touches, puts you in the proper frame of mind for entering into the world of Moby-Dick.

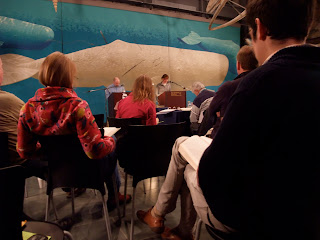

The Mural at MDM15 (and the "longness" of the Whale)

The impressive backdrop at this year's Marathon is the work of Richard Ellis. From the photo, I estimate the length of the painted white whale to be 25 feet.

According to the Wikipedia article "Sperm whale," the whale that sank the Essex was claimed to be 85 feet long, while the Essex itself (do mariners still say "herself"?) was 87 feet long.

For those who attended the opening of the Marathon, the Whaling Museum's half-scale "model" ship, Lagoda, is 89 feet long.

For those who were at the reading of the Cetology chapter, the Museum's juvenile sperm whale skeleton is 48 feet long. According to Chapter 103, Measurement of the Whale's Skeleton, in life this whale would have been about 60 feet long.

Picture yourself in an open whaleboat (25-30 feet long) attacking a beast three times the size of the one in the mural.

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

The Moby-Dick Marathon in Its Psychical Aspect

In his monograph Chasing the White Whale, David Dowling (lecturer in English at the University of Iowa) states that a marathon reading of Moby-Dick is equal parts heaven and hell. While I wouldn't go so far as to say that the hellish part equals the heavenly, there are certainly significant highs and lows during the experience, if you attend the entire reading.

The pre-reading events elicit festive emotions. The attendees are happy to be gathered again to honor their favorite or most-admired novel. On Saturday morning, the museum is filled with lighhearted buzzing, as the staff and volunteers finish their preparations, and the marathoners get themselves arranged for a taxing endeavor.

The Pageant runs from the start of the reading, at noon on Saturday, to the return to the museum from the Seamen's Bethel, around 3 pm. This stage involves the celebrated readers (the Mayor, the U.S. Representative, the National Tour Guide, the Museum Director, the Minister, the District Attorney, et al.) and the dramatic settings (the Lagoda Room and the Bethel). The audience is large. The chapters are among the most familiar and the most conventionally novelistic. The marathoner is alert and attentive to the text.

The Long Stride takes us from mid-afternoon to 10 or 11 at night. At this time, the initial euphoria has worn off, and the participants have settled in for some serious content. We get large doses of philosophical Melville (Ch. XLII, "The Whiteness of the Whale"), scientific Melville (Ch. XXXII, "Cetology"), and Shakespearean Melville (Ch. XL, "Midnight, Forecastle"). Night falls as the summer soldiers, infants, and pensioners decamp one by one.

The Graveyard Shift lasts until about 7 or 8 on Sunday morning. This is when many marathoners grab some sleep. But the die-hards remain at their stations, tending the Melville flame. The gallery is perfectly quiet except for the reader's voice and the occasional whisperings of the "Watch Officers" who manage the process. The marathoner watches the large windows for signs of dawn, pulling his coat about his shoulders as the cold creeps up from the stone floor. Those who continue following the text are treated to Melville's best work.

The Awakening begins between 7 and 8 am and lasts for three or four hours. The light outside and the reinforcement of the museum staff and volunteers (bringing some breakfast food with them) causes the sleepers to rise and tidy up their gear. This is perhaps the most challenging stage, because distractions increase, while the text becomes more flamboyant and less amenable to public reading. A night without sleep while drinking coffee and eating at random takes its toll.

The Final Push then brings the marathon to a close, at approximately 1 pm. At this time, the crowd is as large as it was during the Pageant. The readers, perhaps inspired more by John Huston than by Melville, become excited and demonstrative. For the dedicated marathoner, there is a combination of the elation of having seen the whole thing through and the disappointment at not having been as attentive to the text as one could. You stagger off, exhausted and grimy.

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

The Moby-Dick Marathon in Its Procedural Aspect

But one of the beauties of the New Bedford Moby-Dick marathon is that it attracts precisely those people who are most likely to be excited about the idea of a Moby-Dick marathon. If you're reading this, I assume you're one of them.

The marathon has evolved over the years and will no doubt continue to develop. It is currently a three-day affair. Everything takes place in the New Bedford Whaling Museum except for one side excursion that I will mention in due course. On Friday evening, the marathon proper is heralded by a dinner (reservations required), after which a lecture is given by a Melville scholar. These preliminaries attract, I would estimate, 50-100 people. Next, on Saturday morning, there was this year a new event that I hope will be repeated -- a stump-the-scholars program in which six Melville experts were divided into two teams and competed in trying to answer Moby-Dick-related questions posed by the audience (and in a few cases by the emcee, one of the curators at the museum if I'm not mistaken).

The reading moves to different spots in the museum for two segments: Chapter XXXII (Cetology) is read in the gallery containing a complete sperm whale skeleton, and Chapter XL (Midnight, Forecastle) is performed by a troupe in the auditorium. (This year, they added several other chapters to the auditorium segment.) But by 9:00 or so, we're in the Jacobs Family Gallery for the duration.

Around 6 or 7 pm on Saturday, the gracious volunteers serve clam chowder, baked beans, and bread pudding in an adjoining room. Coffee, tea, and mulled cider are provided through the night, along with assorted snacks (healthy and otherwise). The "break room" is also the place to chat with other marathoners.

Attendance is strongest at the beginning and end of the reading. As Saturday wears on and passes into Sunday, the audience gets thinner and thinner. It hits bottom around, say, 1 to 4 am on Sunday, when there are perhaps as few as 20 people in attendance, half of whom are asleep. Then the crowd returns with the sun on Sunday, waxing until the final crowd-pleasing duel between Ahab and the whale.

Thank yous, acknowledgements, and it's over for another year.

Should one stay or should one go...

Sure it's a bit of a survival stunt to stay with the reading for the entire 25 hours. David Dowling ("Chasing the White Whale") compares the experience to running a road marathon. Unlike road racing, there's no way to train oneself to make "the punishment" less grueling. (...or is there? That's a subject for another post.)

If you commit yourself to the entire event, there are times when it feels like a depression-era dance marathon ("The blood would run out of their shoes," my mother recalled), with the knowledge that there are no cash prizes. And can anyone stay awake, much less concentrate on pithy prose for 25 straight hours? Still, as for the pack-filler at your local road marathon, there is some reward in terms of self-improvement, or "life experience", or bragging rights. (ROFL We should live in such a world.) Then there are moments when you feel like a member of a fading order of priests/priestesses, vainly attempting to preserve "The Word" yet another year against the tide of multi-tasking zombies. "We few, we happy few..."

...be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now-a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here, ...

Oh yeah, there's also the book. It ain't a "Classic" for nothing. There are worlds within worlds there. Each reading broadens my appreciation, highlights details I'd missed, and makes me marvel how a single book can affect so many people across so many cultures.

Anyway... not staying for the entire reading left me feeling incomplete, having missed the point, having abandoned my shipmates in their hour of crisis. Next year I'll be in for the whole book, spend less time taking photos, and take a turn at the podium.

Photos of the 2011 Moby-Dick Marathon

And here's a Flickr set posted by Friends of Ed & Betty. I like the photos here of the Saturday-evening chow line (the volunteers are wonderful!) and the marathoners sacked out on the upper level during the wee hours of Sunday morning.

News of the 2011 Moby-Dick Marathon

Monday, January 10, 2011

Marathon 2011 Has Drawn to a Close

Gansevoort and I lived through another challenging and exhilarating Moby-Dick marathon at the New Bedford Whaling Museum this weekend. Sadly, as a result of bad weather on the road, we missed the pre-marathon lecture Friday evening. But by Saturday morning, we were back on schedule. "Stump the Scholars," a new event, gave six Melville scholars a chance to display their learning in response to audience questions. We also took in the new "Visualizing Melville" exhibit. I bought a marathon T-shirt, offered for the first time this year, and a copy of David Dowling's Chasing the White Whale: The Moby-Dick Marathon; or, What Melville Means Today (signed by the author, who was present).

Neither of us attended the entire marathon this year. I find it more enjoyable to break up the reading with meals and a little sleep. Gansevoort (who, unlike me, is a Barney Frank supporter) was on hand for the start of the marathon reading, back in the Lagoda Room after a year's hiatus. I returned to the museum later in the day and stayed until Sunday morning. Gansevoort hung in longer than I did on Sunday, but he did not stay for the last couple of frenetic hours.

The rest of Sunday was for recuperation, and today I traveled home.